Gesomyrmex, the Amber Javelin Ants Ecology Guide

Gesomyrmex howardi Queen

INTRODUCTION / SUBFAMILY / GENUS

Gesomyrmex is a genus of ants in the subfamily Formicinae. The genus contains seven extant species, and eleven fossil species, about which little is known, since the few species within the genus are rarely encountered. The genus was established by G. Mayr (1868) for a single species from Baltic amber.

Gesomyrmex is a poorly known arboreal ant and are often overlooked elements of the tropical Asian myrmeco fauna.

Members of this genus are very rare and ancient forms as they belong to a loose assemblage of genera which have been considered the most primitive members of the subfamily Formicinae.

These genera, which include Myrmoteras, Gesomyrmex, Gigantiops, Myrmecorhynchus, Opisthopsis and Santschiella, remain among the least studied ants, in spite of their obvious phylogenetic significance.

COMMON NAME

update 28/02/2022: First of all, a big Thank you to Ziv Lieberman (in Facebook) for helping to provide the following etymological explanation.

- Wheeler 1956 says Geso- derives from Greek gaîsos, "javelin" .

As such, this genus should be commonly known as Javelin Ants or better Amber Javelin Ants, while keeping the reference to amber both as color and as the reference to where they were first found.

(I normally like to be as faithful as possible to the translation of their etymological name, but this one of the few times I could not find the meaning for Geso.)

As such, I take this upon myself to commonly name them as Amber Tree Ants. Tree for being arboreal ants and amber since they were first found and the genus created from amber fossils. Nonetheless, let me know if you have other suggestions.

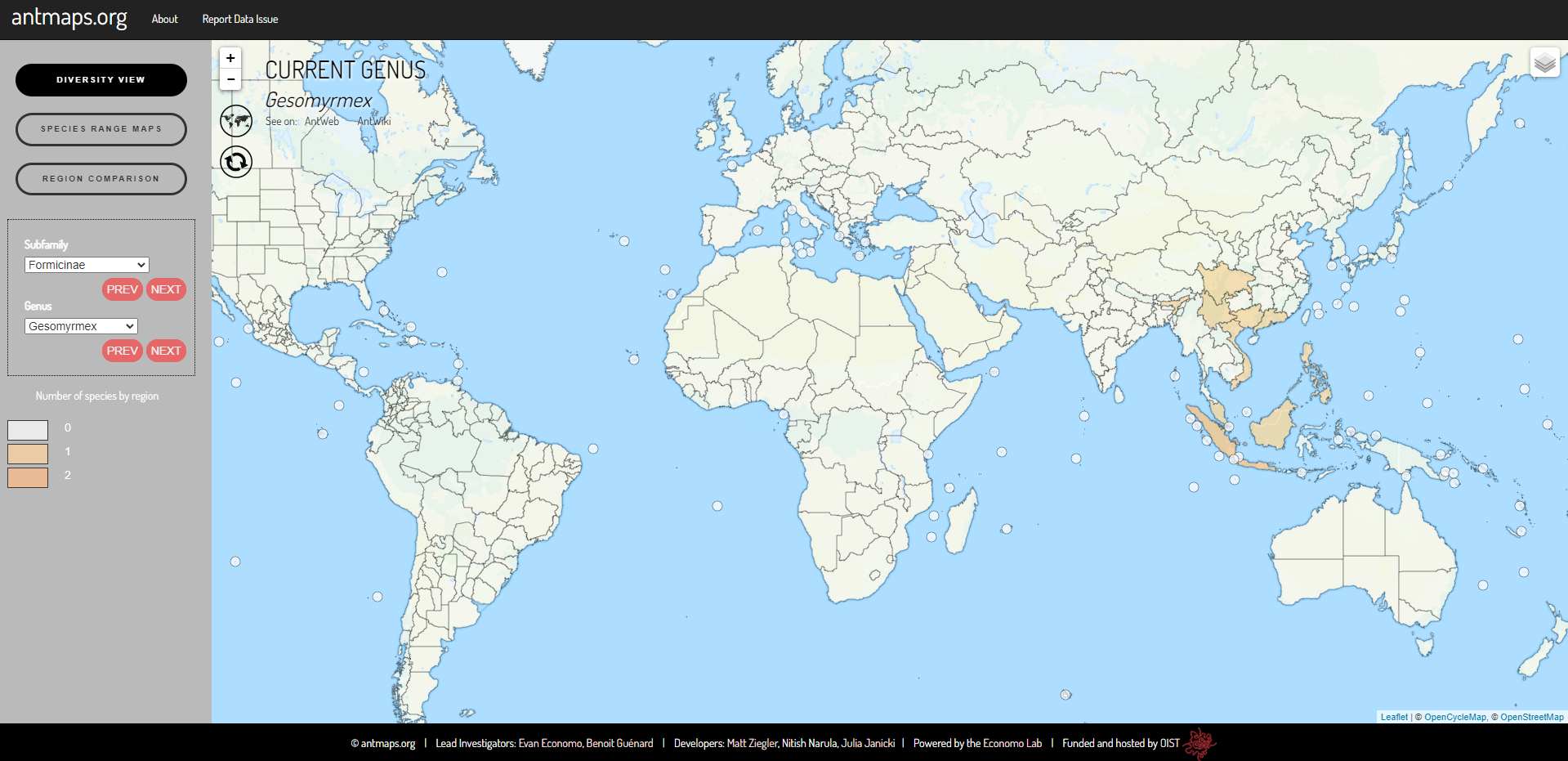

DISTRIBUTION

Antmaps.org - Gesomyrmex Genus

These small, polymorphic formicine ants are native to a variety of forests and mountainous habitats in the Oriental tropics.

The native range of extant Gesomyrmex extends include Borneo, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines and Vietnam.

The fossil records of Gesomyrmex known range from: Baltic amber (Bartonian, Middle to Late Eocene), Bitterfeld amber (Bartonian, Middle to Late Eocene), Bol’shaya Svetlovodnaya, Sikhote-Alin, Russia (Priabonian, Late Eocene), Danish-Scandinavian amber (Bartonian, Middle to Late Eocene), Eckfeld, Germany (Lutetian, Middle Eocene), Messel, Germany (Lutetian, Middle Eocene), Oise amber, France (Ypresian, Early Eocene), Radoboj, Croatia (Burdigalian, Early Miocene), Rovno amber (Priabonian, Late Eocene).

Gesomyrmex Fossil Records

CASTES

Gesomyrmex shows a striking diversity of caste morphologies. In addition to winged queens and drones, depending on the species, between two and three sterile castes can be distinguished using discrete morphological traits, morphometry and total body size.

These ants show a strong polymorphism among castes, with striking size and shape differences between workers, soldiers, and supersoldiers.

Heads of four castes of Gesomyrmex

Worker minima (workers) - Length 2.5 - 3.2 mm

Worker media (soldiers) - Length 3.5 - 4.5 mm

Worker maxima (supersoldiers) - Length 5.0 - 7.0 mm

Drone male - Length - 7.0 to 8.0 mm

Queen - Length nearly - 9.0 mm

MORPHOLOGY AND DIVISION OF LABOR

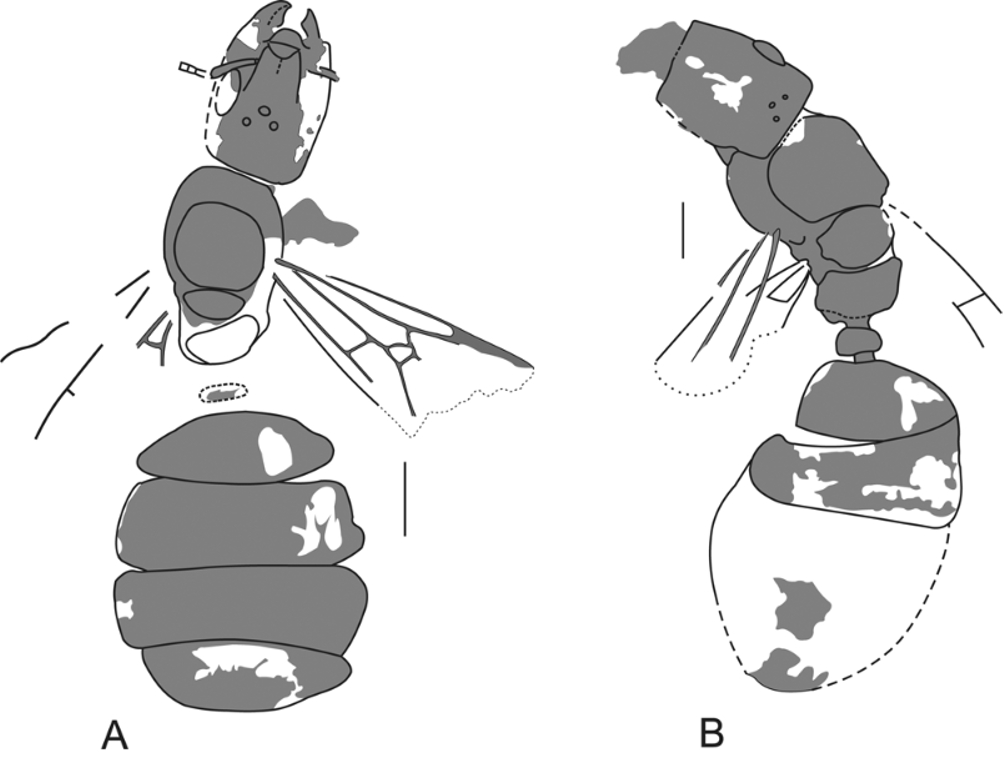

Gesomyrmex presents an intriguing division of labor associated with their extreme polymorphism.

Soldiers and supersoldiers share robust mandibles, the former have square heads, but the latter have a rectangular head and substantially larger body size, like the queens. This suggests both supersoldiers and queens have the muscular power necessary to chew entrance tunnels in healthy wood. Queens and supersoldiers also share frontal lobes (protection for antennal bases), suggesting that they block nest entrances with their heads.

Workers on the other hand, have triangular heads, with thin elongated mandibles with a narrow base and a wide masticatory margin bearing 8-9 sharp teeth.

Gesomyrmex howardi nanitic worker

Disproportionately large and bulging eyes allow overlapping fields of view that result in 3D and lateral vision. Together with nimble piercing mandibles, this confirms that workers hunt live prey in the canopy.

Pupae are naked thus cocoons have been lost as in Oecophylla.

LIFE CYCLE

Gesomyrmex are arboreal ants of the tropical Asian myrmecofauna and observations of their behaviors are a very challenging task to be done in tree canopies. As such there isn’t any information available, as far as my research went, that enabled me to provide any reference numbers for their development periods.

https://blog.myrmecologicalnews.org/2019/12/11/ants-of-hong-kong-sar-china/ - François Brassard Photo

But since I am keeping a colony now, I will try my best to gather this information, and present it to you all at a later date on one of my colony updates.

REPRODUCTIVE STRATEGY

Gesomyrmex ant queens generally start new colonies without any help from workers (which is called independent colony founding, ICF).

In Gesomyrmex, this implies that lone foundresses must first chew an entrance tunnel to the innermost soft pith, and then guard the entrance against intruders for several weeks while they raise the first generation of worker larvae to adulthood.

Gesomyrmex howardi Queen

It is guessed that Gesomyrmex foundresses do not forage outside (i.e. ICF is done as claustral colony foundation), because their mandibles are unsuitable for hunting. The large difference in body size between queens and workers is consistent with claustral ICF, because founding queens can rear workers much smaller than themselves using stored metabolic reserves.

Since supersoldiers have been observed to block nest entrances with their heads, one can assume that queens behave similarly when starting new colonies. Indeed, queens and supersoldiers share frontal lobes (for protection of antennal bases) and sclerotized mandibles.

In all ICF species, the challenge for newly mated foundresses is to rear a first generation of workers as quickly as possible. It is probable that soldiers and especially supersoldiers are reared only after colonies have reached a critical size.

NESTING AND COLONY STRUCTURE

Here follows a nest description for your reference.

The pole was about 2.5m long and was 6.5cm in diameter where the nest was situated. The entrance consisted of four small, slit-like holes, close together and resembling the orifices of beetle burrows. The four entrances were seen to unite to form a single tunnel-like passage, which grew narrower towards the end of the pole and opened into the middle of the main nest-cavity. The two ends of the cavity were rounded out and the wood around the excavated pithy center had been gnawed away to form several irregular galleries. The colony had evidently been nesting in these cavities for some time. The wood was green and solid. The nest chamber (12.5 cm long) in the pithy center of a green branch yielded about 150 adults, one dealate queen, larvae and eggs.

In another study, colonies have been sampled in different localities and examined ten nests inside living branches, yielding some more interesting results.

In none of the nests sampled, the scientists found a reproductive dealate queen, indicating colonies must be polydomous. Eggs were not found inside half of the nests, even though these were 100% complete. This supports the theory for a single queen laying all eggs in one of the nests of a polydomous colony in Gesomyrmex.

The drawbacks of highly secure nests inside living branches is the impossibility to gain additional living space, as such, growing colonies are then forced to expand into additional nests, leading to polydomy. This strategy allows for optimal use of spatial resources and has evolved in many unrelated ants but it presents itself with a challenge.

As written before, it is thought that when founding a nest, newly mated queens need to chew an entrance tunnel that reaches the innermost soft pith. But how do additional nests begin in a colony of Gesomyrmex?

https://blog.myrmecologicalnews.org/2019/12/11/ants-of-hong-kong-sar-china/ - François Brassard Photo

An entrance tunnel must be chewed, but the single reproductive queen is very unlikely to take risks by leaving the safety of her nest. It is speculated that supersoldiers carry out the specialized task of chewing the entrance tunnel of a new nest, and they may be recruited by scouting workers. This likely explains the retention of large eyes in supersoldiers, given they are otherwise restricted to the inside of nests.

Both Queens and supersoldiers share an elongated head with powerful mandibles, an adaptation to chew an entrance tunnel to the innermost pith of living branches.

Supersoldiers are presumably reared even later in colony ontogeny, because they are more costly. Relatively few supersoldiers are present and they show two queen-like behaviors: they stay inside nest chambers and block the entrances, and they chew entrance holes when starting other nests belonging to the same colony as the colony expands. Supersoldiers also store nutrients (trophic eggs) in their gaster.

NEST DEFENSE AND PHRAGMOSIS

As said before, Gesomyrmex are arboreal ants within the Formicinae subfamily, and being formicines, they are of course equipped with formic acid which contributes to their defense capability, but isn’t their main nest defensive strategy.

Attempts to induce Gesomyrmex workers to exit a nest by tapping or hitting it, will be unsuccessful, indicating that their defense strategy consists simply in withdrawing inside their fortress.

Gesomyrmex nest entrance. Photo by Decha Wiwatwitaya

Like other arboreal ant species, Gesomyrmex employs phragmosis, which is a method of closing the burrow or nest by means of some specially adapted part of the body, such as as the flattened head in some ants, like Colobopsis, Cephalotes or Cataulacus.

If phragmosis is broadly defined as blocking nest entrances with a body part, two extremes are distinct across ants:

(i) In Cephalotes, Colobopsis and a few other genera, soldiers have highly modified heads that match exactly the shape of nest entrances;

(ii) In Cataulacus and others, blocking behavior is not associated with dramatic modifications in head shape. In Gesomyrmex, the same occurs, where conspicuously rectangular heads reflect enlarged mandible muscles, but the dorsal cranium is not used to plug the nest entrance. Instead, a broader head together with sturdy mandibles combine to block entrances. A compromise is thus apparent between powerful mandibles and evolving plug-shaped heads.

Supersoldier head blocking the entrance. Photo by Decha Wiwatwitaya

FORAGING AND FEEDING

As said before functional morphology can be used to predict the specialized functions of different castes. And it is confirmed that workers are the active hunters in the colony due to their large eyes and very distinct mandibles.

This can also be confirmed by observing them during their foraging activities. It has been described that workers run with a jerky zigzag gait and are very agile on tree trunks

As regarding feeding preferences, there isn’t any available bibliography on this topic, and from my experience, I can only say that honeywater was very well received by the Queen and its lone worker.

Feeding small insect prey will be attempted at a later stage, and this post updated accordingly.

Gesomyrmex howardi nanitic worker

CONCLUSION

Gesomyrmex genus still raises many questions for scientists.

The five taxonomically isolated lineages correspond to the genera Gesomyrmex, Gigantiops, Myrmoteras, Oecophylla, and Santschiella. which are all based on single archaic, relict genera of large-eyed ants.

The phylogenomic data do suggest partial resolution of their positions in the formicine tree, including placement of Myrmoteras as sister to Camponotini, and a sister-group relationship of Oecophylla and Gesomyrmex as well as Gigantiops and Santschiella, but these still deserves further investigation.

As an example, the thickened bases of the emora of G. howardi indicate that this ant can jump like the large-eyed Gigantiops destructor and share other similar morphological traits with Myrmoteras.

Hope you have enjoyed reading this article about the “Amber Javelin Ants” and unfortunately this time I don’t have any video for you.

I will try to provide some of my own footage soon! But meanwhile, you can check this short little video on the link down below!

Thank you for your time to read this article!

Cheers!

Gesomyrmex howardi Queen